As shown on the map, the Great Wall offered some protection to travelers between what two cities?

| Bully Wall of China | |

|---|---|

| 萬里長城 / 万里长城 | |

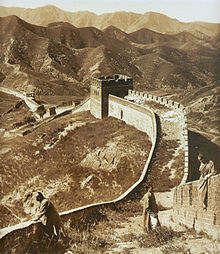

The Ming dynasty Great Wall at Jinshanling | |

Map of all the wall constructions | |

| General information | |

| Type | Fortification |

| Country | Prc |

| Coordinates | twoscore°41′N 117°14′E / 40.68°N 117.23°E / 40.68; 117.23 Coordinates: 40°41′N 117°fourteen′E / 40.68°Due north 117.23°E / 40.68; 117.23 |

| Technical details | |

| Size | 21,196.eighteen km (13,170.70 mi)[one] [2] [3] |

| UNESCO World Heritage Site | |

| Official name | The Slap-up Wall |

| Type | Cultural |

| Criteria | i, ii, iii, iv, vi |

| Designated | 1987 (11th session) |

| Reference no. | 438 |

| State Party | China |

| Region | Asia-Pacific |

| Dandy Wall of China | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Chinese | 長城 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 长城 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Literal pregnant | "The Long Wall" | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Alternative Chinese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 萬里長城 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 万里长城 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | "The 10,000-li Long Wall" | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Great Wall of China (traditional Chinese: 萬里長城; simplified Chinese: 万里长城; pinyin: Wànlǐ Chángchéng ) is a series of fortifications that were congenital across the historical northern borders of aboriginal Chinese states and Imperial China as protection against various nomadic groups from the Eurasian Steppe. Several walls were built from as early equally the 7th century BC,[four] with selective stretches later joined together by Qin Shi Huang (220–206 BC), the first emperor of China. Little of the Qin wall remains.[5] Later on, many successive dynasties built and maintained multiple stretches of border walls. The best-known sections of the wall were congenital by the Ming dynasty (1368–1644).

Apart from defense, other purposes of the Great Wall have included edge controls, allowing the imposition of duties on goods transported along the Silk Road, regulation or encouragement of merchandise and the command of immigration and emigration.[6] Furthermore, the defensive characteristics of the Great Wall were enhanced by the structure of watchtowers, troop barracks, garrison stations, signaling capabilities through the means of fume or fire, and the fact that the path of the Great Wall also served as a transportation corridor.

The frontier walls built by dissimilar dynasties have multiple courses. Collectively, they stretch from Liaodong in the east to Lop Lake in the w, from the present-day Sino–Russian border in the northward to Tao River (Taohe) in the south; along an arc that roughly delineates the edge of the Mongolian steppe; spanning 21,196.xviii km (13,170.70 mi) in total.[7] [three] Today, the defensive system of the Peachy Wall is generally recognized equally one of the most impressive architectural feats in history.[8]

Names

Huayi tu, a 1136 map of China with the Smashing Wall depicted on the northern edge of the country

The collection of fortifications known equally the Great Wall of China has historically had a number of unlike names in both Chinese and English language.

In Chinese histories, the term "Long Wall(south)" ( t 長城, s 长城, Chángchéng) appears in Sima Qian'south Records of the 1000 Historian, where it referred both to the split up swell walls congenital betwixt and due north of the Warring States and to the more unified construction of the Beginning Emperor.[9] The Chinese graphic symbol 城 , meaning urban center or fortress, is a phono-semantic compound of the "earth" radical 土 and phonetic 成 , whose Old Chinese pronunciation has been reconstructed as *deŋ.[ten] Information technology originally referred to the rampart which surrounded traditional Chinese cities and was used by extension for these walls around their respective states; today, however, it is much more than often the Chinese word for "city".[eleven]

The longer Chinese proper noun "Ten-Thousand Mile Long Wall" ( t 萬里長城, southward 万里长城, Wànlǐ Chángchéng) came from Sima Qian's clarification of it in the Records, though he did not proper noun the walls as such. The Ad 493 Book of Song quotes the frontier general Tan Daoji referring to "the long wall of 10,000 miles", closer to the modern proper noun, but the name rarely features in pre-modern times otherwise.[12] The traditional Chinese mile ( 里 , lǐ) was an oft irregular altitude that was intended to show the length of a standard village and varied with terrain but was usually standardized at distances around a 3rd of an English language mile (540 m).[xiii] However, this apply of "ten-thousand" (wàn) is figurative in a similar manner to the Greek and English myriad and simply ways "innumerable" or "immeasurable".[fourteen]

Because of the wall'southward association with the Start Emperor's supposed tyranny, the Chinese dynasties after Qin usually avoided referring to their own additions to the wall past the name "Long Wall".[fifteen] Instead, various terms were used in medieval records, including "borderland(s)" ( 塞 , Sài),[xvi] "rampart(s)" ( 垣 , Yuán),[xvi] "barrier(s)" ( 障 , Zhàng),[16] "the outer fortresses" ( 外堡 , Wàibǎo),[17] and "the border wall(s)" (t 邊牆 , southward 边墙 , Biānqiáng).[15] Poetic and informal names for the wall included "the Purple Frontier" ( 紫塞 , Zǐsài)[18] and "the Earth Dragon" (t 土龍 , southward 土龙 , Tǔlóng).[nineteen] Only during the Qing flow did "Long Wall" become the grab-all term to refer to the many border walls regardless of their location or dynastic origin, equivalent to the English "Not bad Wall".[xx]

Sections of the wall in south Gobi Desert and Mongolian steppe are sometimes referred to as "Wall of Genghis Khan", even though Genghis Khan did not construct any walls or permanent defense lines himself.[21]

The current English name evolved from accounts of "the Chinese wall" from early modernistic European travelers.[xx] By the nineteenth century,[xx] "the Dandy Wall of China" had get standard in English and French, although other European languages such as High german continue to refer to it as "the Chinese wall".[14]

History

Early walls

The Great Wall of the Qin stretches from Lintao to Liaodong

The Chinese were already familiar with the techniques of wall-building past the time of the Leap and Autumn menses between the 8th and 5th centuries BC.[22] During this time and the subsequent Warring States period, the states of Qin, Wei, Zhao, Qi, Han, Yan, and Zhongshan[23] [24] all constructed extensive fortifications to defend their own borders. Built to withstand the attack of pocket-size arms such as swords and spears, these walls were fabricated by and large of stone or by stamping earth and gravel between board frames.

The Smashing Wall of the Han is the longest of all walls, from Mamitu about Yumenguan to Liaodong

King Zheng of Qin conquered the last of his opponents and unified Cathay as the Start Emperor of the Qin dynasty ("Qin Shi Huang") in 221 BC. Intending to impose centralized rule and prevent the resurgence of feudal lords, he ordered the devastation of the sections of the walls that divided his empire among the sometime states. To position the empire against the Xiongnu people from the north, however, he ordered the building of new walls to connect the remaining fortifications along the empire's northern frontier. "Build and movement on" was a central guiding principle in constructing the wall, implying that the Chinese were not erecting a permanently fixed border.[25] Transporting the big quantity of materials required for construction was difficult, so builders ever tried to employ local resource. Stones from the mountains were used over mountain ranges, while rammed earth was used for construction in the plains. There are no surviving historical records indicating the exact length and course of the Qin walls. Nigh of the ancient walls accept eroded away over the centuries, and very few sections remain today. The human cost of the structure is unknown, only it has been estimated by some authors that hundreds of thousands[26] workers died building the Qin wall. Subsequently, the Han,[27] the Northern dynasties and the Sui all repaired, rebuilt, or expanded sections of the Great Wall at groovy toll to defend themselves confronting northern invaders.[28] The Tang and Song dynasties did not undertake any significant effort in the region.[28] Dynasties founded past non-Han indigenous groups also congenital their border walls: the Xianbei-ruled Northern Wei, the Khitan-ruled Liao, Jurchen-led Jin and the Tangut-established Western Xia, who ruled vast territories over Northern China throughout centuries, all synthetic defensive walls merely those were located much to the north of the other Swell Walls every bit nosotros know it, inside China'south autonomous region of Inner Mongolia and in modernistic-twenty-four hours Mongolia itself.[29]

Ming era

The Great Wall concept was revived again under the Ming in the 14th century,[xxx] and following the Ming army's defeat past the Oirats in the Boxing of Tumu. The Ming had failed to gain a articulate upper hand over the Mongol tribes subsequently successive battles, and the long-drawn conflict was taking a toll on the empire. The Ming adopted a new strategy to go along the nomadic tribes out by constructing walls forth the northern border of China. Acknowledging the Mongol control established in the Ordos Desert, the wall followed the desert's southern border instead of incorporating the bend of the Yellow River.

Unlike the earlier fortifications, the Ming structure was stronger and more than elaborate due to the utilise of bricks and rock instead of rammed world. Up to 25,000 watchtowers are estimated to have been constructed on the wall.[31] Equally Mongol raids continued periodically over the years, the Ming devoted considerable resources to repair and reinforce the walls. Sections near the Ming capital of Beijing were especially strong.[32] Qi Jiguang between 1567 and 1570 also repaired and reinforced the wall, faced sections of the ram-earth wall with bricks and synthetic 1,200 watchtowers from Shanhaiguan Pass to Changping to warn of approaching Mongol raiders.[33] During the 1440s–1460s, the Ming besides built a so-chosen "Liaodong Wall". Similar in part to the Great Wall (whose extension, in a sense, it was), but more than basic in construction, the Liaodong Wall enclosed the agricultural heartland of the Liaodong province, protecting it against potential incursions by Jurchen-Mongol Oriyanghan from the northwest and the Jianzhou Jurchens from the north. While stones and tiles were used in some parts of the Liaodong Wall, most of it was in fact simply an earth dike with moats on both sides.[34]

Towards the end of the Ming, the Great Wall helped defend the empire against the Manchu invasions that began around 1600. Fifty-fifty after the loss of all of Liaodong, the Ming ground forces held the heavily fortified Shanhai Laissez passer, preventing the Manchus from conquering the Chinese heartland. The Manchus were finally able to cross the Bully Wall in 1644, after Beijing had already fallen to Li Zicheng's short-lived Shun dynasty. Before this fourth dimension, the Manchus had crossed the Great Wall multiple times to raid, but this fourth dimension it was for conquest. The gates at Shanhai Pass were opened on May 25 by the commanding Ming general, Wu Sangui, who formed an alliance with the Manchus, hoping to utilize the Manchus to expel the rebels from Beijing.[35] The Manchus quickly seized Beijing, and somewhen defeated both the Shun dynasty and the remaining Ming resistance, consolidating the rule of the Qing dynasty over all of China proper.[36]

Nether Qing dominion, People's republic of china's borders extended beyond the walls and Mongolia was annexed into the empire, so constructions on the Groovy Wall were discontinued. On the other hand, the and so-called Willow Palisade, following a line like to that of the Ming Liaodong Wall, was constructed by the Qing rulers in Manchuria. Its purpose, however, was not defence force but rather to foreclose Han Chinese migration into Manchuria.[37]

Foreign accounts

Part of the Bully Wall of China (April 1853, 10, p. 41)[38]

None of the Europeans who visited China or Mongolia in the 13th and 14th centuries, such as Giovanni da Pian del Carpine, William of Rubruck, Marco Polo, Odoric of Pordenone and Giovanni de' Marignolli, mentioned the Great Wall.[39] [40]

The North African traveler Ibn Battuta, who as well visited China during the Yuan dynasty c. 1346, had heard about China's Slap-up Wall, perchance before he had arrived in China.[41] He wrote that the wall is "sixty days' travel" from Zeitun (modern Quanzhou) in his travelogue Souvenir to Those Who Contemplate the Wonders of Cities and the Marvels of Travelling. He associated it with the fable of the wall mentioned in the Qur'an,[42] which Dhul-Qarnayn (unremarkably associated with Alexander the Neat) was said to have erected to protect people virtually the land of the rising sun from the savages of Gog and Magog. However, Ibn Battuta could find no one who had either seen it or knew of anyone who had seen it, suggesting that although there were remnants of the wall at that time, they were not significant.[43]

Soon subsequently Europeans reached Ming China by transport in the early on 16th century, accounts of the Great Wall started to broadcast in Europe, even though no European was to run into it for another century. Peradventure 1 of the primeval European descriptions of the wall and of its significance for the defence force of the country against the "Tartars" (i.east. Mongols) may be the one independent in João de Barros's 1563 Asia.[44] Other early accounts in Western sources include those of Gaspar da Cruz, Bento de Goes, Matteo Ricci, and Bishop Juan González de Mendoza,[45] the latter in 1585 describing information technology as a "superbious and mightie work" of architecture, though he had not seen it.[46] In 1559, in his piece of work "A Treatise of China and the Adjoyning Regions", Gaspar da Cruz offers an early on give-and-take of the Peachy Wall.[45] Perhaps the first recorded case of a European actually inbound China via the Not bad Wall came in 1605, when the Portuguese Jesuit brother Bento de Góis reached the northwestern Jiayu Pass from India.[47] Early European accounts were mostly pocket-sized and empirical, closely mirroring contemporary Chinese understanding of the Wall,[48] although later they slid into hyperbole,[49] including the erroneous but ubiquitous merits that the Ming walls were the same ones that were built past the beginning emperor in the third century BC.[49]

When China opened its borders to strange merchants and visitors after its defeat in the First and Second Opium Wars, the Peachy Wall became a master allure for tourists. The travelogues of the subsequently 19th century further enhanced the reputation and the mythology of the Great Wall.[l]

Course

A formal definition of what constitutes a "Great Wall" has not been agreed upon, making the full form of the Corking Wall difficult to describe in its entirety.[51] The defensive lines incorporate multiple stretches of ramparts, trenches and ditches, as well as individual fortresses.

In 2012, based on existing inquiry and the results of a comprehensive mapping survey, the National Cultural Heritage Assistants of China concluded that the remaining Great Wall associated sites include 10,051 wall sections, 1,764 ramparts or trenches, 29,510 individual buildings, and 2,211 fortifications or passes, with the walls and trenches spanning a total length of 21,196.xviii km (13,170.70 mi).[three] Incorporating advanced technologies, the report has concluded that the Ming Cracking Wall measures 8,850 km (five,500 mi).[52] This consists of 6,259 km (3,889 mi) of wall sections, 359 km (223 mi) of trenches and 2,232 km (one,387 mi) of natural defensive barriers such equally hills and rivers.[52] In improver, Qin, Han and before Great Wall sites are 3,080 km (1,914 mi) long in total; Jin dynasty (1115–1234) border fortifications are 4,010 km (two,492 mi) in length; the remainder engagement back to Northern Wei, Northern Qi, Sui, Tang, the Five Dynasties, Vocal, Liao and Xixia.[3] About one-half of the sites are located in Inner Mongolia (31%) and Hebei (19%).[3]

Han Nifty Wall

Han fortifications starts from Yumen Laissez passer and Yang Pass, southwest of Dunhuang, in Gansu province. Ruins of the remotest Han edge posts are establish in Mamitu ( t 馬迷途 , s 马迷途 , Mǎmítú, l "horses losing their fashion") near Yumen Pass.

Ming Nifty Wall

The Jiayu Pass, located in Gansu province, is the western terminus of the Ming Great Wall. From Jiayu Pass the wall travels discontinuously down the Hexi Corridor and into the deserts of Ningxia, where it enters the western edge of the Yellow River loop at Yinchuan. Here the kickoff major walls erected during the Ming dynasty cut through the Ordos Desert to the eastern border of the Yellow River loop. There at Piantou Pass (t 偏頭關 , s 偏头关 , Piāntóuguān) in Xinzhou, Shanxi province, the Bang-up Wall splits in 2 with the "Outer Great Wall" (t 外長城 , s 外长城 , Wài Chǎngchéng) extending forth the Inner Mongolia edge with Shanxi into Hebei province, and the "Inner Keen Wall" (t 內長城 , southward 內长城 , Nèi Chǎngchéng) running southeast from Piantou Pass for some 400 km (250 mi), passing through important passes like the Pingxing Pass and Yanmen Pass before joining the Outer Great Wall at Sihaiye ( 四海冶 , Sìhǎiyě), in Beijing'southward Yanqing Canton.

The sections of the Slap-up Wall around Beijing municipality are especially famous: they were oftentimes renovated and are regularly visited by tourists today. The Badaling Great Wall near Zhangjiakou is the well-nigh famous stretch of the wall, for this was the get-go section to be opened to the public in the People's Commonwealth of People's republic of china, as well equally the showpiece stretch for foreign dignitaries.[53] The Badaling Dandy Wall saw nearly x million visitors in 2018, and in 2019, a daily limit of 65,000 visitors was instated.[54] South of Badaling is the Juyong Laissez passer; when it was used by the Chinese to protect their land, this section of the wall had many guards to defend the capital Beijing. Fabricated of stone and bricks from the hills, this portion of the Nifty Wall is 7.8 g (25 ft 7 in) high and 5 m (16 ft 5 in) wide.

One of the most striking sections of the Ming Smashing Wall is where information technology climbs extremely steep slopes in Jinshanling. At that place it runs 11 km (7 mi) long, ranges from v to viii m (16 ft 5 in to 26 ft 3 in) in elevation, and 6 one thousand (xix ft 8 in) across the bottom, narrowing upwardly to 5 m (16 ft five in) across the height. Wangjing Lou (t 望京樓 , s 望京楼 , Wàngjīng Lóu) is 1 of Jinshanling's 67 watchtowers, 980 yard (3,220 ft) to a higher place sea level. Southeast of Jinshanling is the Mutianyu Cracking Wall which winds forth lofty, cragged mountains from the southeast to the northwest for ii.25 km (1.40 mi). It is connected with Juyongguan Pass to the west and Gubeikou to the due east. This section was one of the first to be renovated post-obit the turmoil of the Cultural Revolution.[55]

At the edge of the Bohai Gulf is Shanhai Pass, considered the traditional end of the Keen Wall and the "Offset Laissez passer Under Heaven". The part of the wall inside Shanhai Pass that meets the body of water is named the "Old Dragon Head". 3 km (2 mi) north of Shanhai Pass is Jiaoshan Peachy Wall ( t 焦山長城, s 焦山长城, Jiāoshān Chángchéng), the site of the first mountain of the Groovy Wall.[56] fifteen km (9 mi) northeast from Shanhaiguan is Jiumenkou (t 九門口 , south 九门口 , Jiǔménkǒu), which is the only portion of the wall that was built as a bridge.

In 2009, 180 km of previously unknown sections of the Ming wall concealed past hills, trenches and rivers were discovered with the help of infrared range finders and GPS devices.[57] In March and April 2015, nine sections with a full length of more than ten km (6 mi), believed to be part of the Corking Wall, were discovered along the edge of Ningxia autonomous region and Gansu province.[58]

Characteristics

Before the use of bricks, the Great Wall was mainly built from rammed earth, stones, and forest. During the Ming, however, bricks were heavily used in many areas of the wall, as were materials such as tiles, lime, and rock. The size and weight of the bricks made them easier to piece of work with than earth and stone, so construction quickened. Additionally, bricks could bear more weight and endure better than rammed earth. Stone can hold under its own weight amend than brick, but is more difficult to employ. Consequently, stones cutting into rectangular shapes were used for the foundation, inner and outer brims, and gateways of the wall. Battlements line the uppermost portion of the vast majority of the wall, with defensive gaps a little over 30 cm (12 in) tall, and about 23 cm (nine.1 in) wide. From the parapets, guards could survey the surrounding country.[59] Communication betwixt the army units along the length of the Slap-up Wall, including the ability to call reinforcements and warn garrisons of enemy movements, was of high importance. Bespeak towers were built upon hill tops or other high points along the wall for their visibility. Wooden gates could be used every bit a trap confronting those going through. Barracks, stables, and armories were built near the wall's inner surface.[59]

Condition

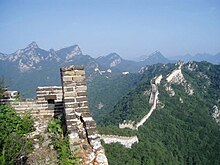

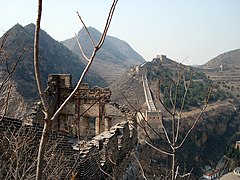

A more rural portion of the Keen Wall that stretches through the mountains, here seen in slight disrepair

While portions northward of Beijing and near tourist centers have been preserved and even extensively renovated, in many other locations the wall is in disrepair. The wall sometimes provided a source of stones to build houses and roads.[threescore] Sections of the wall are also prone to graffiti and vandalism, while inscribed bricks were pilfered and sold on the marketplace for up to 50 renminbi.[61] Parts have been destroyed to make way for structure or mining.[62] A 2012 report by the National Cultural Heritage Administration states that 22% of the Ming Slap-up Wall has disappeared, while i,961 km (one,219 mi) of wall have vanished.[61] More than than 60 km (37 mi) of the wall in Gansu province may disappear in the adjacent 20 years, due to erosion from sandstorms. In some places, the height of the wall has been reduced from more 5 m (16 ft v in) to less than 2 one thousand (6 ft seven in). Diverse square sentry towers that characterize the most famous images of the wall have disappeared. Many western sections of the wall are synthetic from mud, rather than brick and stone, and thus are more susceptible to erosion.[63] In 2014 a portion of the wall near the border of Liaoning and Hebei province was repaired with concrete. The piece of work has been much criticized.[64]

Visibility from space

From the Moon

The notion that the wall can be seen from the moon (with an boilerplate orbital radius of 385,000 km (239,000 miles)) is a well-known but untrue myth.[65]

I of the earliest known references to the myth that the Great Wall can exist seen from the moon appears in a letter of the alphabet written in 1754 past the English antiquary William Stukeley. Stukeley wrote that, "This mighty wall [Hadrian'southward wall] of four score miles [130 km] in length is only exceeded by the Chinese Wall, which makes a considerable figure upon the terrestrial globe, and may be discerned at the Moon."[66] The claim was also mentioned by Henry Norman in 1895 where he states "besides its age it enjoys the reputation of being the merely work of human being easily on the earth visible from the Moon."[67] The issue of "canals" on Mars was prominent in the late 19th century and may have led to the belief that long, sparse objects were visible from space. The claim that the Keen Wall is visible from the moon also appears in 1932's Ripley'due south Believe Information technology or Not! strip.[68]

The claim that the Great Wall is visible from the moon has been debunked many times[69] (the credible width of the Great Wall from the Moon would be the aforementioned equally that of a human hair viewed from three km (ii mi) away[seventy]) but is even so ingrained in popular civilisation.[71]

From depression World orbit

Identical satellite images of a section of the Great Wall in northern Shanxi, running diagonally from lower left to upper right and not to exist dislocated with the more than prominent river running from upper left to lower right. In the image on the right, the Keen Wall has been outlined in red. The region pictured is 12 km × 12 km (7 mi × 7 mi).

A more controversial question is whether the wall is visible from low Earth orbit (an distance of as niggling equally 160 km (100 mi)). NASA claims that it is barely visible, and merely under nearly perfect conditions; it is no more than conspicuous than many other human being-made objects.[72]

Veteran US astronaut Gene Cernan has stated: "At Earth orbit of 100 to 200 miles [160 to 320 km] high, the Smashing Wall of China is, indeed, visible to the naked eye." Ed Lu, Expedition seven Science Officeholder aboard the International Infinite Station, adds that, "It's less visible than a lot of other objects. And you lot have to know where to look."

In Oct 2003, Chinese astronaut Yang Liwei stated that he had not been able to run into the Keen Wall of Communist china. In response, the European Space Bureau (ESA) issued a printing release reporting that from an orbit between 160 and 320 km (100 and 200 mi), the Great Wall is visible to the naked eye.[70]

Leroy Chiao, a Chinese-American astronaut, took a photograph from the International Space Station that shows the wall. It was so indistinct that the photographer was not certain he had actually captured it. Based on the photo, the China Daily after reported that the Great Wall can be seen from 'space' with the naked eye, under favorable viewing conditions, if one knows exactly where to await.[73] [70]

Gallery

-

"The Starting time Mound" – at Jiayu Pass, the western terminus of the Ming wall

-

The Slap-up Wall about Jiayu Laissez passer

-

The Great Wall remnant at Yulin

-

The Juyongguan area of the Keen Wall accepts numerous tourists each day

-

Environmental protection sign virtually Swell Wall, 2011

-

Ming Great Wall at Simatai, overlooking the gorge

-

Mutianyu Swell Wall. This is atop the wall on a section that has non been restored

-

The Old Dragon Head, the Great Wall where it meets the sea in the vicinity of Shanhai Laissez passer

-

The Great Wall at dawn

-

Inside the watchtower

-

Badaling Great Wall during wintertime

See also

- Cheolli Jangseong

- Chinese urban center wall

- Defense of the Smashing Wall

- Gates of Alexander

- Great Wall of Cathay hoax

- Groovy Wall Marathon

- Great Wall of Gorgan

- Great Wall of Republic of india

- List of World Heritage Sites in China

- Miaojiang Smashing Wall

- Offa'south Dyke

- Roman military frontiers and fortifications

- Zasechnaya cherta

Notes

- ^ "People's republic of china'south Great Wall Plant To Measure More 20,000 Kilometers". Bloomberg. June 5, 2012. Retrieved June six, 2012.

- ^ "China's Great Wall is 'longer than previously thought'". BBC News. June 6, 2012. Archived from the original on December 5, 2021. Retrieved December 28, 2021.

- ^ a b c d due east 中国长城保护报告 [Protection Report of the Great Wall of People's republic of china]. National Cultural Heritage Administration.

- ^ The New York Times with introduction by Sam Tanenhaus (2011). The New York Times Guide to Essential Knowledge: A Desk-bound Reference for the Curious Mind. St. Martin'due south Press of Macmillan Publishers. p. 1131. ISBN978-0-312-64302-seven.

Beginning as carve up sections of fortification around the 7th century B.C.E and unified during the Qin Dynasty in the tertiary century B.C.Eastward, this wall, built of world and rubble with a facing of brick or stone, runs from east to west beyond Communist china for over 4,000 miles.

- ^ "Great Wall of China". Encyclopædia Britannica.

Large parts of the fortification system appointment from the 7th through the 4th century BC. In the third century BC Shihuangdi (Qin Shi Huang), the kickoff emperor of a united China (under the Qin dynasty), connected a number of existing defensive walls into a unmarried organisation. Traditionally, the eastern terminus of the wall was considered to be Shanhai Pass (Shanhaiguan) on the declension of the Bohai (Gulf of Zhili), and the wall'due south length—without its branches and other secondary sections—was idea to extend for some 6,690 km (iv,160 mi).

- ^ Shelach-Lavi, Gideon; Wachtel, Ido; Golan, Dan; Batzorig, Otgonjargal; Amartuvshin, Chunag; Ellenblum, Ronnie; Honeychurch, William (June 2020). "Medieval long-wall construction on the Mongolian Steppe during the eleventh to thirteenth centuries AD". Antiquity. 94 (375): 724–741. doi:10.15184/aqy.2020.51. ISSN 0003-598X.

- ^ "Great Wall of Cathay even longer than previously thought". Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. June 6, 2012. Retrieved June half-dozen, 2012.

- ^ "Great Wall of China". History. Apr twenty, 2009.

- ^ Waldron 1983, p. 650.

- ^ Baxter, William H. & al. (September 20, 2014). "Baxter–Sagart Old Chinese Reconstruction, Version i.1" (PDF). Ann Arbor: University of Michigan. Retrieved Jan 22, 2015.

- ^ See Lovell 2006, p. 25

- ^ Waldron 1990, p. 202. Tan Daoji's exact quote: "So you would destroy your Bully Wall of Ten Thousand Li!" (乃復壞汝萬里之長城) Note the use of the particle 之 zhi that differentiates the quote from the modern name.

- ^ Byron R. Winborn (1994). Wen Bon: a Naval Air Intelligence Officer behind Japanese lines in Red china. Academy of North Texas Press. p. 63. ISBN978-0-929398-77-viii.

- ^ a b Lindesay, William (2007). The Great Wall Revisited: From the Jade Gate to Old Dragon'southward Head. Beijing: Wuzhou Publishing. p. 21. ISBN978-7-5085-1032-3.

- ^ a b Waldron 1983, p. 651.

- ^ a b c Lovell 2006, p. 15.

- ^ Waldron 1990, p. 49.

- ^ Waldron 1990, p. 21.

- ^ Waldron 1988, p. 69.

- ^ a b c Hessler 2007, p. 59.

- ^ Man, John (2008). "6. WALL-Hunt IN THE GOBI". The Bang-up Wall: The extraordinary history of Prc's wonder of the earth. TRANSWORLD PUBLISHERS LTD. pp. 132–148. ISBN9780553817683.

- ^ 歷代王朝修長城 (in Chinese). Chiculture.net. Retrieved October 24, 2010.

- ^ 古代长城 – 战争与和平的纽带 (in Chinese). Newsmth.cyberspace. Retrieved Oct 24, 2010.

- ^ 万里长城 (in Chinese). Newsmth.net. Retrieved October 24, 2010.

- ^ Burbank, Jane; Cooper, Frederick (2010). Empires in World History: Power and the Politics of Difference. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Printing. p. 45.

- ^ Slavicek, Mitchell & Matray 2005, p. 35.

- ^ Coonan, Clifford (February 27, 2012). "British researcher discovers piece of Bang-up Wall 'marooned outside China'". The Irish gaelic Times . Retrieved Feb 28, 2012.

- ^ a b Waldron 1983, p. 653.

- ^ Waldron 1983, p. 654; Haw 2006, pp. 52–54.

- ^ Karnow 2008, p. 192.

- ^ Szabó, Dávid & Loczy 2010, p. 220.

- ^ Evans 2006, p. 177.

- ^ "Groovy Wall at Mutianyu". Smashing Wall of China. Archived from the original on March 9, 2013.

- ^ Edmonds 1985, pp. 38–40.

- ^ Lovell 2006, p. 254.

- ^ Elliott 2001, pp. one–ii.

- ^ Elliott, Mark C. "The Limits of Tartary: Manchuria in Imperial and National Geographies". Journal of Asian Studies 59, no. 3 (2000): 603–646.

- ^ "Part of the Groovy Wall of Red china". The Wesleyan Juvenile Offering: A Miscellany of Missionary Information for Young Persons. X: 41. April 1853. Retrieved February 29, 2016.

- ^ Ruysbroek, Willem van (1900) [1255]. The Journeying of William of Rubruck to the Eastern Parts of the World, 1253–55, equally Narrated by Himself, with Two Accounts of the Earlier Journeying of John of Pian de Carpine. Translated from the Latin past William Woodville Rockhill. London: The Hakluyt Society.

- ^ Haw 2006, pp. 53–54.

- ^ Haw 2006, pp. 54–55.

- ^ Qur'an, Xviii: "The Cavern". English translations hosted at Wikisource include Maulana Muhammad Ali's, Due east.H. Palmer'due south, and the Progressive Muslims Organization'southward.

- ^ Haw 2006, pp. 53–55.

- ^ Barros, João de (1777) [1563]. Ásia de João de Barros: Dos feitos que bone portugueses fizeram no descobrimento dos mares eastward terras exercise Oriente. Vol. V. Lisbon: Lisboa. 3a Década, pp. 186–204 (originally Vol. Ii, Ch. vii).

- ^ a b Waldron 1990, pp. 204–05.

- ^ Lach, Donald F (1965). Asia in the Making of Europe. Vol. I. The University of Chicago Press. p. 769.

- ^ Yule 1866, p. 579This section is the report of Góis'due south travel, as reported by Matteo Ricci in De Christiana expeditione apud Sinas (published 1615), annotated by Henry Yule).

- ^ Waldron 1990, pp. 2–4.

- ^ a b Waldron 1990, p. 206.

- ^ Waldron 1990, p. 209.

- ^ Hessler 2007, p. lx.

- ^ a b "Great Wall of China 'even longer'". BBC. April 20, 2009. Retrieved April xx, 2009.

- ^ Rojas 2010, p. 140.

- ^ Askhar, Aybek. "Limit placed on number of visitors to Great Wall". China Daily . Retrieved August 10, 2020.

- ^ Lindesay 2008, p. 212.

- ^ "Jiaoshan Great Wall". TravelChinaGuide.com . Retrieved September 15, 2010.

Jiaoshan Great Wall is located about 3 km (ii mi) from Shanhaiguan ancient urban center. It is named afterward Jiaoshan Mountain, which is the highest tiptop to the n of Shanhai Laissez passer and likewise the first mountain the Slap-up Wall climbs up after Shanhai Pass. Therefore Jiaoshan Mountain is noted as "The showtime mountain of the Great Wall".

- ^ "Not bad Wall of China longer than believed equally 180 missing miles found". The Guardian. Associated Press. April xx, 2009. Retrieved April 18, 2015.

- ^ "Newly-discovered remains redraw path of Corking Wall". Mainland china Daily. April 15, 2015. Archived from the original on April xviii, 2015. Retrieved April 18, 2015.

- ^ a b Turnbull 2007, p. 29.

- ^ Ford, Peter (November 30, 2006). New police to keep People's republic of china's Wall looking dandy. Christian Science Monitor, Asia Pacific section. Retrieved March 17, 2007.

- ^ a b Wong, Edward (June 29, 2015). "Red china Fears Loss of Groovy Wall, Brick past Brick". The New York Times . Retrieved July 1, 2015.

- ^ Bruce G. Doar: The Great Wall of Mainland china: Tangible, Intangible and Destructible. Mainland china Heritage Newsletter, China Heritage Project, Australian National University

- ^ "China's Wall condign less and less Peachy". Reuters. August 29, 2007. Retrieved Baronial thirty, 2007.

- ^ Ben Westcott; Serenitie Wang (September 21, 2016). "China's Great Wall covered in cement". CNN.

- ^ "NASA - Communist china'south Wall Less Keen in View from Space". www.nasa.gov . Retrieved June 7, 2021.

- ^ The Family Memoirs of the Rev. William Stukeley (1887) Vol. 3, p. 142. (1754).

- ^ Norman, Henry, The Peoples and Politics of the Far East, p. 215. (1895).

- ^ ""The Great Wall of Communist china", Ripley'south Believe It or Not!, 1932.

- ^ Urban Legends.com website. Accessed May 12, 2010.

"Tin can yous come across the Great Wall of China from the moon or outer infinite?", Answers.com. Accessed May 12, 2010.

Cecil Adams, "Is the Swell wall of People's republic of china the only manmade object byou tin can encounter from space?", The Straight Dope. Accessed May 12, 2010.

Snopes, "Great wall from space", last updated July 21, 2007. Accessed May 12, 2010.

"Is Mainland china's Great Wall Visible from Space?", Scientific American, Feb 21, 2008. "... the wall is only visible from low orbit nether a specific set of weather and lighting atmospheric condition. And many other structures that are less spectacular from an earthly vantage point—desert roads, for example—appear more prominent from an orbital perspective." - ^ a b c López-Gil 2008, pp. 3–iv.

- ^ "Metro Tescos", The Times (London), Apr 26, 2010. Establish at The Times website. Accessed May 12, 2010.

- ^ "NASA – Great Wall of China". Nasa.gov. Retrieved July 31, 2010.

- ^ Markus, Francis. (April 19, 2005). Great Wall visible in infinite photo. BBC News, Asia-Pacific department. Retrieved March 17, 2007.

References

- Edmonds, Richard Louis (1985). Northern Frontiers of Qing China and Tokugawa Nippon: A Comparative Study of Borderland Policy. University of Chicago, Section of Geography; Research Paper No. 213. ISBN978-0-89065-118-vi.

- Elliott, Mark C. (2001). The Manchu Manner: The Viii Banners and Ethnic Identity in Tardily Imperial China. Stanford University Press. ISBN978-0-8047-4684-7.

- Evans, Thammy (2006). Neat Wall of Mainland china: Beijing & Northern China. Bradt Travel Guide. Bradt Travel Guides. p. 3. ISBN978-1-84162-158-6.

- Haw, Stephen G. (2006). Marco Polo's Cathay: a Venetian in the realm of Khubilai Khan. Book iii of Routledge studies in the early history of Asia. Psychology Press. ISBN978-0-415-34850-viii.

- Hessler, Peter (2007). "Letter from China: Walking the Wall". The New Yorker. No. May 21, 2007. pp. 58–67.

- Karnow, Mooney, Paul and Catherine (2008). National Geographic Traveler: Beijing. National Geographic Books. p. 192. ISBN978-i-4262-0231-five.

- Lindesay, William (2008). The Smashing Wall Revisited: From the Jade Gate to Old Dragon'due south Head. Harvard University Press. ISBN978-0-674-03149-iv.

- López-Gil, Norberto (2008). "Is information technology Really Possible to See the Great Wall of China from Space with a Naked Heart?" (PDF). Journal of Optometry. 1 (1): 3–iv. doi:10.3921/joptom.2008.3. PMC3972694. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 10, 2008.

- Lovell, Julia (2006). The Great Wall : China against the earth 1000 BC – AD 2000. Sydney: Picador Pan Macmillan. ISBN978-0-330-42241-iii.

- Rojas, Carlos (2010). The Great Wall : a cultural history. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. ISBN978-0-674-04787-7.

- Slavicek, Louise Chipley; Mitchell, George J.; Matray, James I. (2005). The Bully Wall of Red china. Infobase Publishing. p. 35. ISBN978-0-7910-8019-one.

- Szabó, József; Dávid, Lóránt; Loczy, Denes, eds. (2010). Anthropogenic Geomorphology: A Guide to Man-made Landforms. Springer. ISBN978-xc-481-3057-three.

- Turnbull, Stephen R (January 2007). The Peachy Wall of China 221 BC–Advertisement 1644. Osprey Publishing. ISBN978-ane-84603-004-8.

- Waldron, Arthur (1983). "The Problem of The Great Wall of People's republic of china". Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies. 43 (2): 643–663. doi:10.2307/2719110. JSTOR 2719110.

- Waldron, Arthur (1988). "The Peachy Wall Myth: Its Origins and Part in Modernistic China". The Yale Periodical of Criticism. 2 (1): 67–104.

- Waldron, Arthur (1990). The Great Wall of China: from history to myth . Cambridge England New York: Cambridge University Printing. ISBN978-0-521-42707-4.

- Yule, Sir Henry, ed. (1866). Cathay and the way thither: beingness a drove of medieval notices of China. Issues 36–37 of Works issued past the Hakluyt Club. Printed for the Hakluyt guild.

Farther reading

- Arnold, H. J. P., "The Not bad Wall: Is It or Isn't It?" Astronomy Now, 1995.

- Beckwith, Christopher I. (2009): Empires of the Silk Road: A History of Central Eurasia from the Statuary Age to the Nowadays. Princeton: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-13589-two.

- Luo, Zewen, et al. and Baker, David, ed. (1981). The Great Wall. Maidenhead: McGraw-Colina Volume Company (Great britain). ISBN 0-07-070745-6

- Man, John. (2008). The Corking Wall. London: Runted Press. 335 pages. ISBN978-0-593-05574-8.

- Michaud, Roland and Sabrina (photographers), & Michel January, The Groovy Wall of China. Abbeville Press, 2001. ISBN 0-7892-0736-two

- Schafer, Edward H. (1985). The Golden Peaches of Samarkand. Berkeley: Academy of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-05462-2.

- Yamashita, Michael; Lindesay, William (2007). The Bully Wall – From Starting time to End. New York: Sterling. 160 pages. ISBN978-i-4027-3160-0.

External links

- International Friends of the Great Wall Archived February 17, 2009, at the Wayback Machine – organization focused on conservation

- UNESCO Earth Heritage Centre profile

- Enthusiast/scholar website (in Chinese)

- Great Wall of Mainland china on In Our Time at the BBC

- Photoset of bottom visited areas of the Great Wall

-

Geographic data related to Groovy Wall of Mainland china at OpenStreetMap

Geographic data related to Groovy Wall of Mainland china at OpenStreetMap

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Great_Wall_of_China

0 Response to "As shown on the map, the Great Wall offered some protection to travelers between what two cities?"

Post a Comment